Tar Sands Threaten World’s Largest Boreal Forest

By Rachael Petersen, Nigel Sizer and Peter Lee

Photo by Ken Owen.

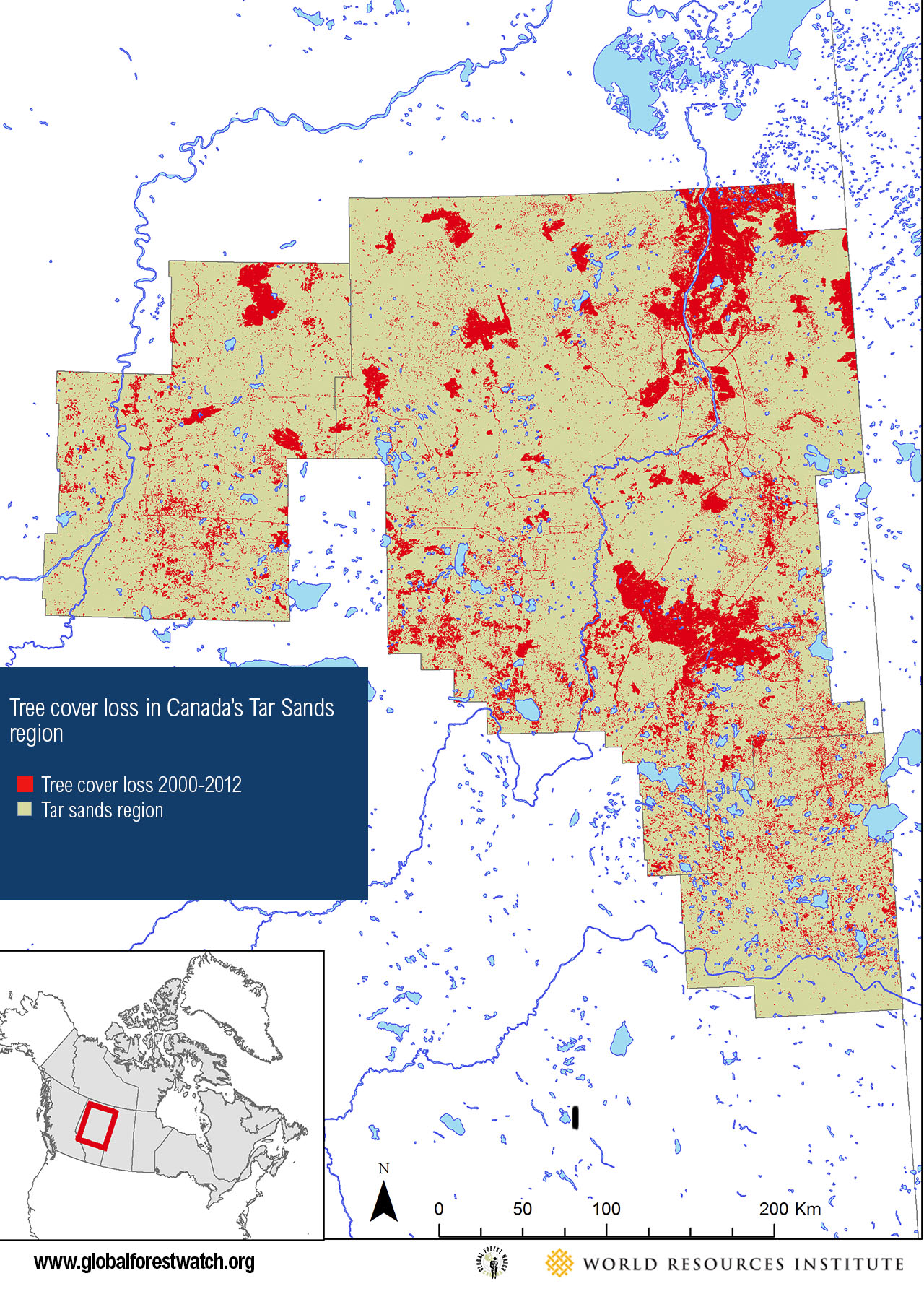

Photo by Ken Owen.Canada’s boreal forest is one of Earth’s major ecological treasures. Yet the region’s forests are under threat from logging, hydrodams and mining. Satellite data reveals a major new threat to Canada’s boreal forests—tar sands development. According to data from Global Forest Watch, an online mapping platform that monitors forests in near-real time, industrial development and forest fires in Canada’s tar sands region has cleared or degraded 775,500 hectares (almost two million acres) of boreal forest since the year 2000 (Map A). That’s an area more than six times the size of New York City. If the tar sands extraction boom continues, as many predict, we can expect forest loss to increase.

MAP A: Tree cover loss of 775,500 hectares in Canada’s Tar Sands region 2000-2012.

MAP A: Tree cover loss of 775,500 hectares in Canada’s Tar Sands region 2000-2012.Mapping World’s Largest Boreal Forest

Only recently have we begun to understand how important boreal forests are to Canada—and to the world. WRI and partners—including Global Forest Watch Canada—began researching forest cover change in the boreal region in the late 1990s. We examined more than 1,000 satellite images of the forested area, mapping every road, oil and gas well site, mine, farm, and other operations. We found that Canada houses the world’s largest ecologically intact boreal forest, with 54 percent of world’s total. The region stretches more than 500 million hectares (1.24 billion acres) roughly 14 times the size of California.

Canada’s boreal forests are also incredibly diverse, featuring mountain ranges; forested plains, bogs, and peatlands; coniferous and mixed forests; and millions of waterways. They support wildlife ranging from gray wolves to black bears to the endangered woodland caribou. They are also home and vital sources of livelihoods and culture for hundreds of First Nations communities, such as the Cree Nation. And because boreal forests capture and store twice as much carbon dioxide as tropical forests, the area plays a critical, global role in curbing climate change.

A Region Under Threat

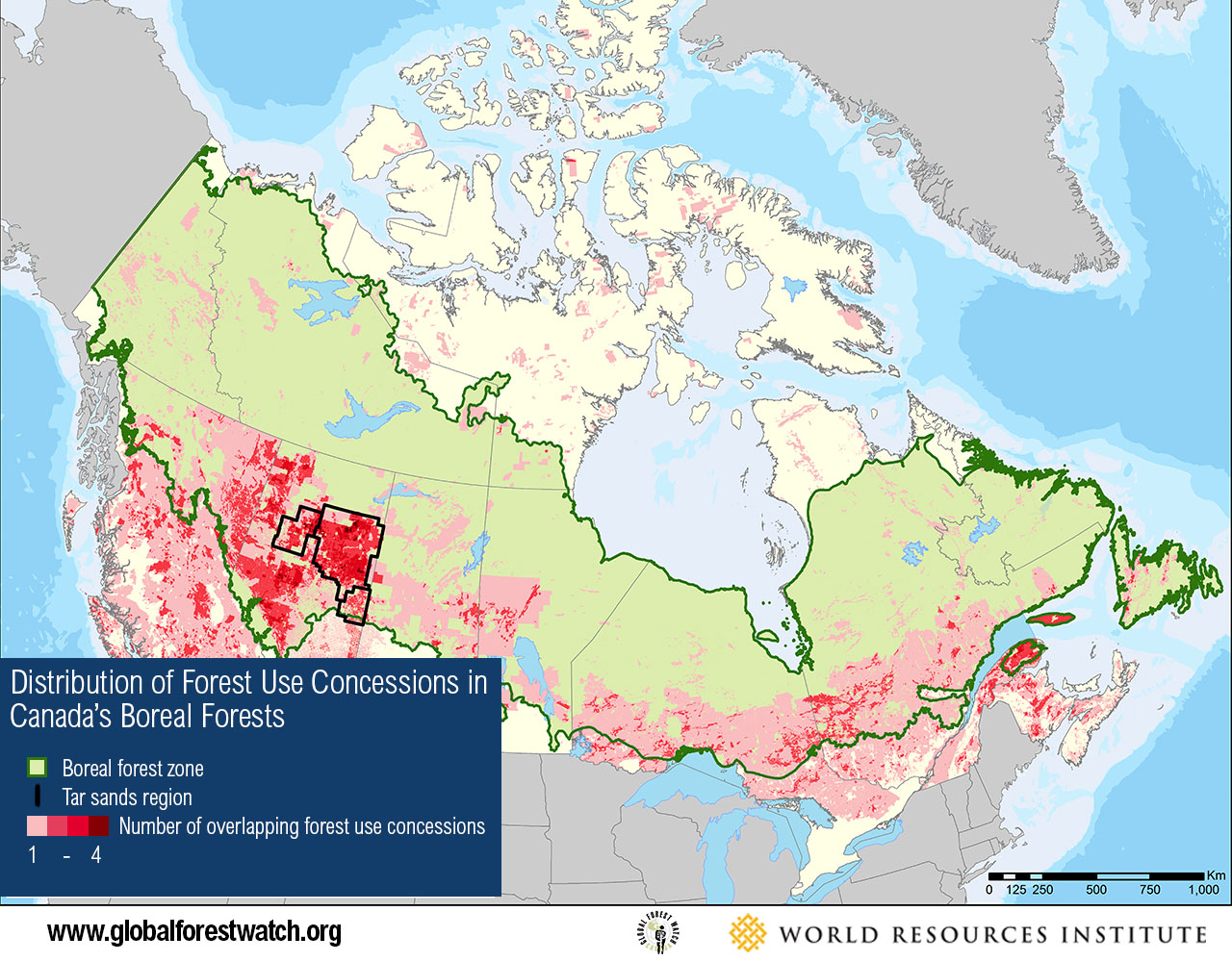

According to Global Forest Watch data, from 2000-2013, Canada lost more than 26 million hectares of forest, mainly in its boreal region. More than 20 percent of the boreal forest region (more than 150 million hectares) is now covered by industrial concessions for timber operations, hydrocarbon development, hydroelectric power reservoirs, and mineral extraction (Map B).

MAP B: Industrial Concessions Cover 150 million hectares of Canada’s Boreal Forest

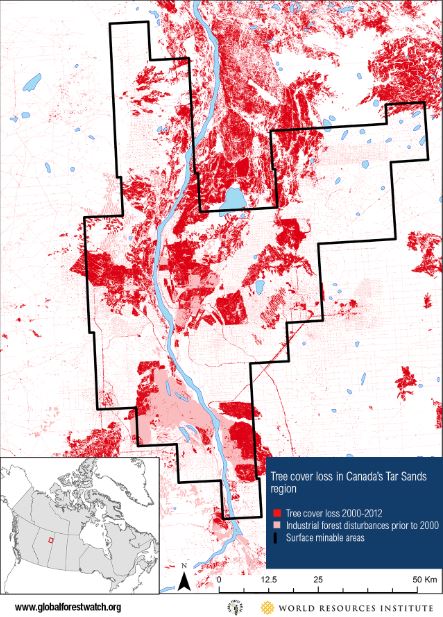

MAP B: Industrial Concessions Cover 150 million hectares of Canada’s Boreal ForestForest loss is particularly high in the Alberta tar sands region, an area covering about 14 million hectares. Between 2000 and 2012, forest loss in the tar sands region—which is caused by bitumen (oil) extraction as well as logging and other industrial development—amounted to 5.5 percent of total land area, surpassing loss in Russia (2.2 percent), the United States (2.9 percent), Brazil (4.3 percent) and Canada as a whole (3.1 percent). And in the surface mineable area of the tar sands region—a 475,000 hectare area within the tar sands region where developers clear all vegetation from the land in order to extract bitumen—forest loss reached 20 percent (Map C).

MAP C: Tree cover loss of 20 percent in tar sands surface mineable area, 2000-2012

MAP C: Tree cover loss of 20 percent in tar sands surface mineable area, 2000-2012And it’s not just forests that suffer from surface mining. For example, studies indicate that woodland caribou avoid areas within 500 meters of industrial disturbances, and will not cross cleared areas as forest is fragmented, making the ecological footprint of tar sands disturbances much larger than the physical footprint. More than 12.5 million hectares of this region have experienced habitat disruption due mainly to tar sands development.

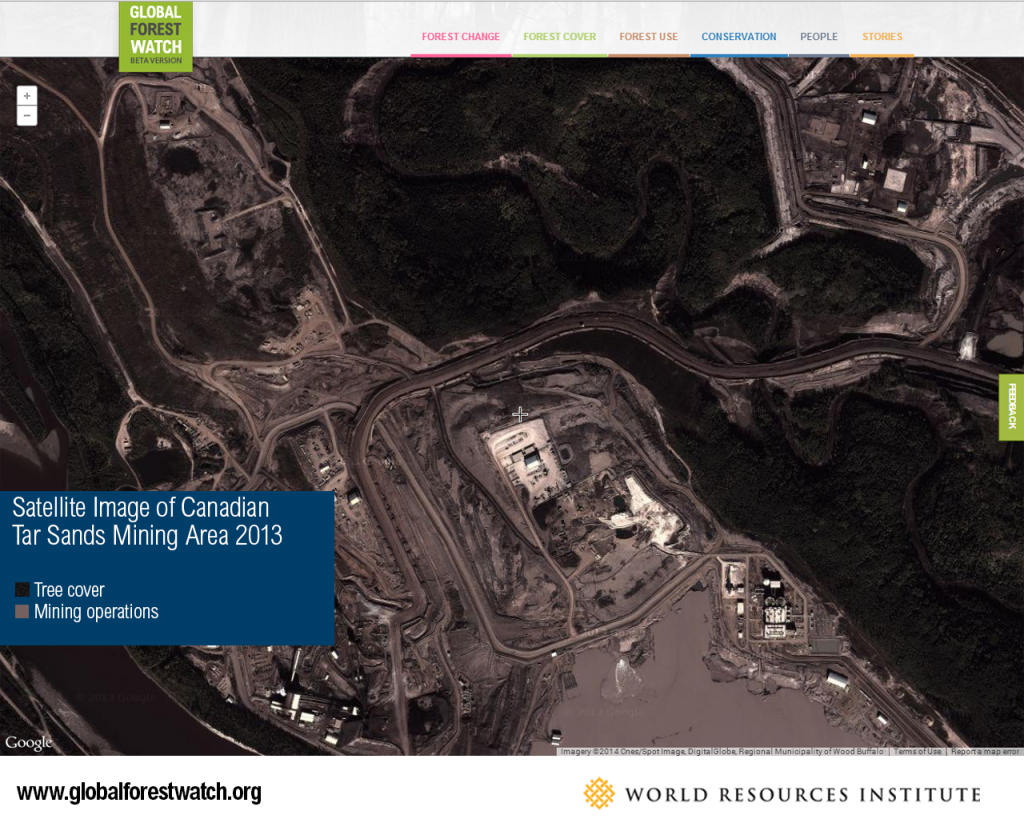

Eyes in the Sky for Boreal Forests

Many predict that Canada’s tar sands development will continue to accelerate. Direct forest loss caused by surface and sub-surface tar sands development is projected to exceed 1,150,000 hectares over the next few decades. Studies show that disrupted habitat for endangered species will be at least 10 times that amount.

But there is hope: Global Forest Watch provides a whole new level of transparency for Canada’s boreal forests. We can produce maps of where companies are operating throughout the boreal region. Regularly updated satellite imagery at medium and fine resolutions allows us to see how forests are changing, spot where forest loss is occurring, and identify potential culprits. This data provides a consistent basis on which to quantify threats to the boreal ecosystem. In short, NGOs and other forest stakeholders can use tools like GFW to assess what’s going on in the boreal forest, hold companies and government agencies accountable, and encourage the government and other decision-makers to enact better forest protections. It’s too late to prevent the damage that’s already been done to Canada’s boreal forest. But with “eyes in the sky,” we may be better able to help protect and properly manage this critical ecosystem for future generations.