Global Forest Watch and the Forest Resources Assessment, Explained in 5 Graphics

Global Forest Watch and Forest Resources Assessment

Today, we have more data about forests than ever before, but we still can’t seem to agree on where, when and why forests are changing around the world. Even two prominent global data sources appear to disagree, at least on the surface. “Deforestation continues globally, if at a slower pace” was the headline of the 2020 Global Forest Resources Assessment (FRA) published by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). At the same time, Global Forest Watch (GFW) reported that “primary rainforest destruction increased 12% from 2019 to 2020.”

What gives? Unfortunately, the answer is not simple. Both GFW and FRA provide valuable information on the state of global forests, but they differ substantially in terms of purpose, scope and approach. By answering questions on how and why these two global data sources differ, we can begin to see them as complementary rather than contradictory. Ultimately, our knowledge of global forests remains incomplete, and we need all the information we can get.

GFW is an independent online forest monitoring platform launched in 2014 by a consortium of partners led by World Resources Institute. GFW seeks to empower forest managers, law enforcement officers and other forest stakeholders with free access to timely and high-resolution data about the current status of forests and recent forest change. GFW uses satellite technology to monitor tree cover loss worldwide with weekly and annual updates, as well as to provide 20-year tree cover gain and net change data. Gain, net change and annual loss data are GFW’s core data sets and are provided by the University of Maryland. Other data sets on GFW provide useful contextual information related to forests and forest change.

The FRA, which the FAO has published at 5- to 10-year intervals since 1946, seeks to provide a consistent and comprehensive approach to describing the world’s forests and how they are changing. Countries provide reports to FRA based on data from National Forest Inventories, satellite data and extrapolation based on past data. The FAO combines the data submitted by countries into global reports and fills in any gaps where data is not available from the countries. The most recent edition of the FRA in 2020 included national-level statistics on more than 60 ecological and socio-economic variables reported by 236 countries and territories.

What is considered a “forest”?

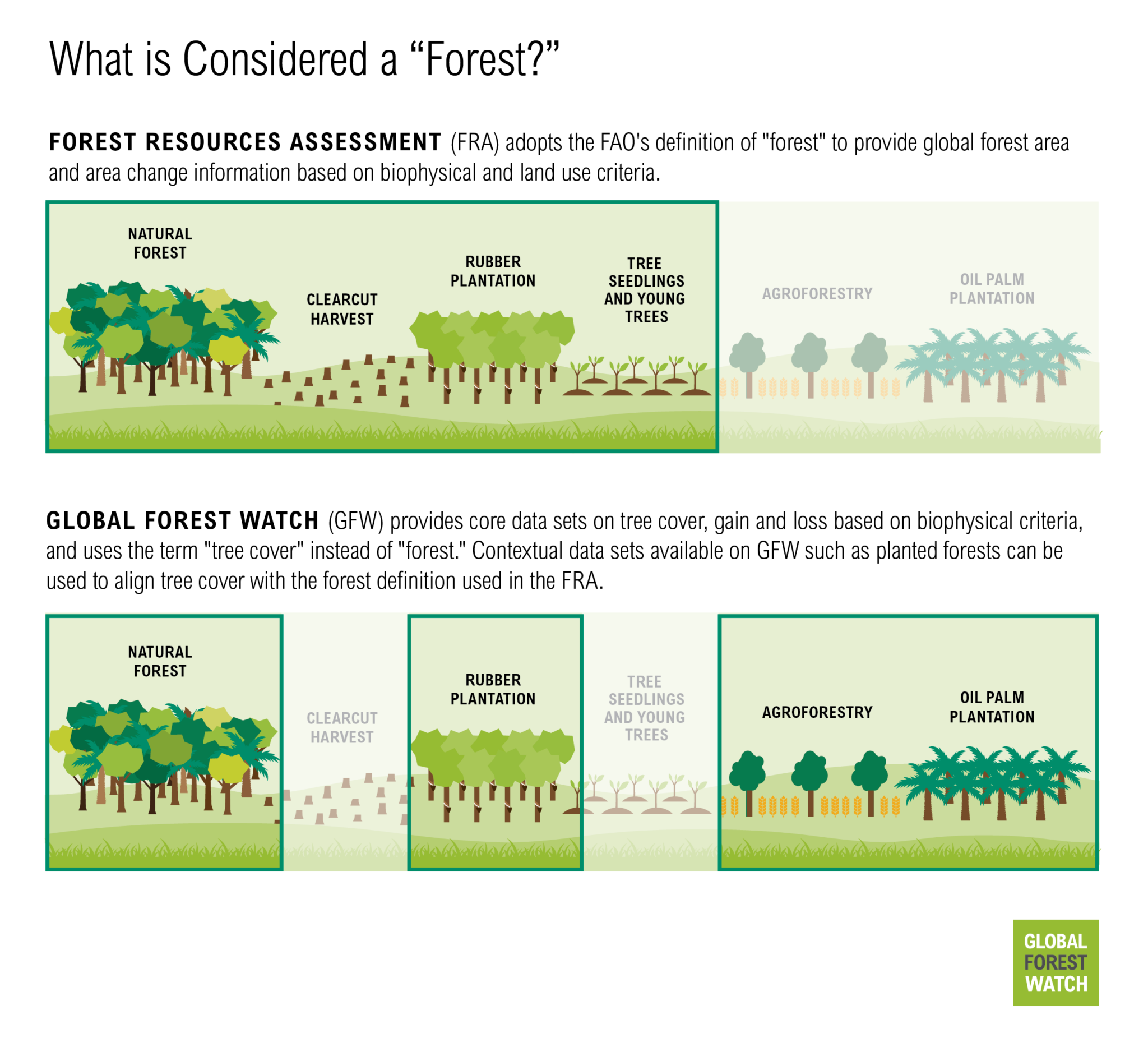

GFW and FRA both talk about “forests,” but what are they actually measuring and monitoring? There are more than 800 definitions of “forest” in use, which only adds to the confusion.

Every five years, FRA publishes forest area globally and per country. These area measurements are based on a standardized definition of “forest” adopted by the FAO in 2000, which takes into account biophysical and land use criteria. The biophysical criterion establishes minimum thresholds for the height, canopy cover and extent of trees. The land use criterion requires that land be officially or legally designated for a “forest use,” such as conservation or harvest. Land that contains trees but is designated for agricultural or urban uses — for example, an oil palm plantation, shade grown cocoa (agroforestry) or a city park — would not be considered a forest. At the same time, land that is temporarily devoid of trees — for example, recently logged or burned areas — would still be classified as forest if the official land use stipulates that trees will be allowed to regenerate in the future.

GFW provides data on “tree cover,” which is derived from satellite data and therefore cannot discern intended land use. Thus, GFW’s monitoring systems rely entirely on biophysical criteria — related to height, canopy cover and extent of trees. GFW does not adopt a specific definition of forest, but rather monitors all forms of tree cover including natural forests and tree plantations. Using GFW’s interactive online platform, users can filter this data based on their preferred definition of forest. Users can select by canopy cover percent, as well as tree height. Users can also view other data sets that give additional context on the land use such primary forests and planted trees.

How is “forest change” reported?

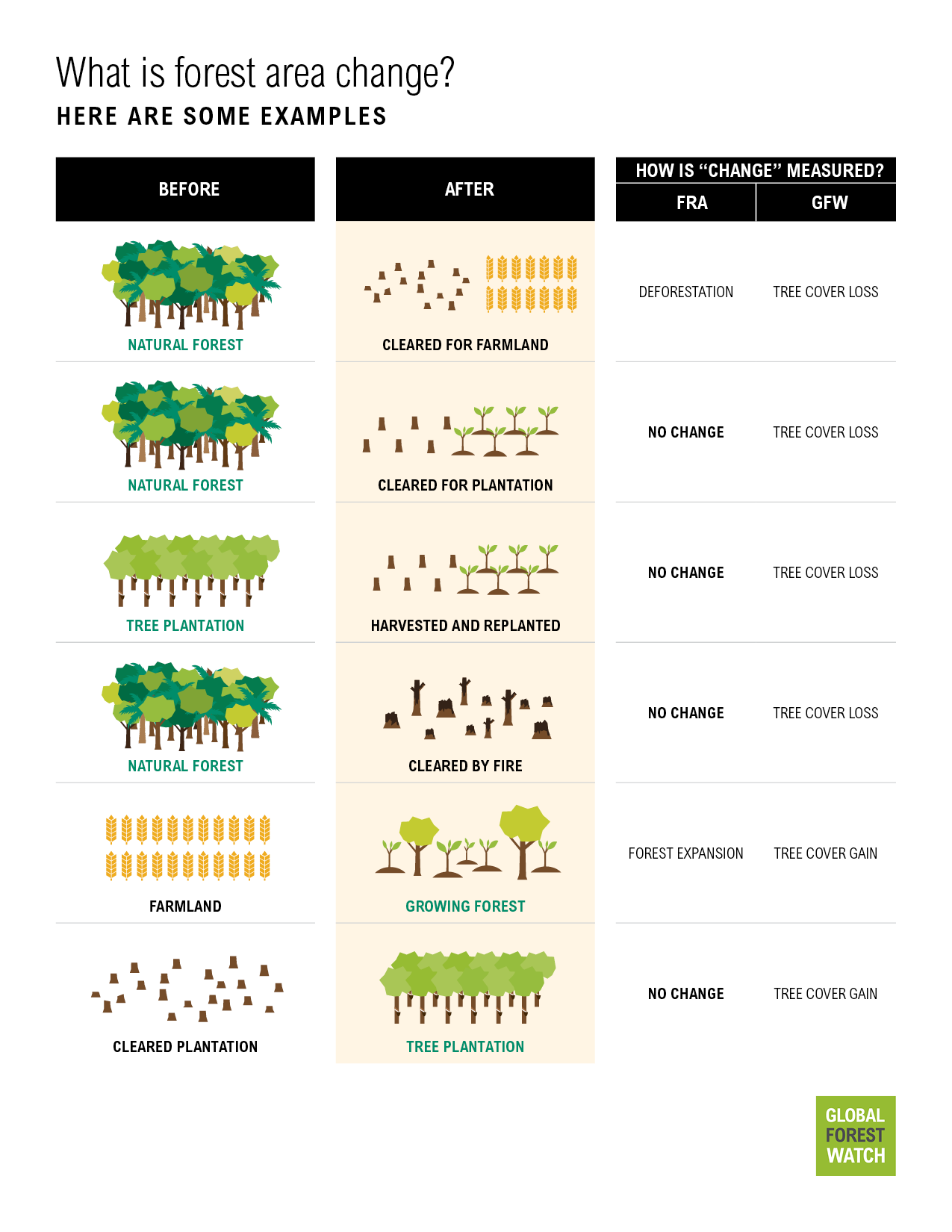

Both FRA and GFW aggregate monitoring data into global statistics about forest change. Like the different ways they measure forests, GFW and FRA apply different lenses to monitor changes to forests, which subsequently influence how both forest expansion and deforestation are reported. GFW reports annual gross loss of tree cover, as well as gross gain and net change for a 20-year period. FRA reports on deforestation, net change and forest expansion as separate statistics, though many countries only report forest area, from which net change can be derived.

Deforestation and tree cover loss

Using its land use criterion, the FAO’s definition of deforestation requires permanent land use change to occur. Losses of tree cover considered to be temporary (e.g., forests that have been clear cut but will be left to regrow) are not counted as deforestation.

Conversely, GFW detects and reports all instances of tree cover loss, regardless of whether the loss will be temporary or permanent (e.g., clear cut harvest followed by agriculture). As with forests, GFW does not seek to define deforestation but rather allows users to filter tree cover loss data based on their own preferred definition.

Though GFW data includes all forms of tree cover loss, data on certain drivers of loss is available on GFW, such as tree cover loss due to fires and tree cover loss by dominant driver, the latter of which can be used to better align with the definition of deforestation used by FRA. GFW uses the tree cover loss by dominant driver data to create a “deforestation proxy” consisting of tree cover loss due to shifting agricultural expansion into primary forests, commodity-driven deforestation and urbanization.

FRA deforestation data is available for the 5- or 10-year reporting periods, while GFW tree cover loss data is available annually.

Forest expansion, tree cover gain and reforestation

As with the deforestation data, information on forest expansion is available for the FRA reporting periods of 5 or 10 years. In FRA, forest expansion can be due to afforestation or a natural expansion of forest area.

GFW data on tree cover gain is available for a 20-year time period, 2000-2020. Like with the tree cover data, GFW gain data includes regrowth in plantations following harvesting, which would not be included in forest expansion according to FRA.

FRA also provides reforestation data, which does not influence forest area or their net change figure. FRA defines reforestation as the planting of trees in areas already considered as forests by FAO’s land use criterion.

Forest area and tree cover net change

FRA and GFW report net change in forest and tree cover extent respectively. As with the tree cover gain data, the GFW net change data currently only compares 2000 to 2020. FRA data is available for their 5- or 10-year reporting periods.

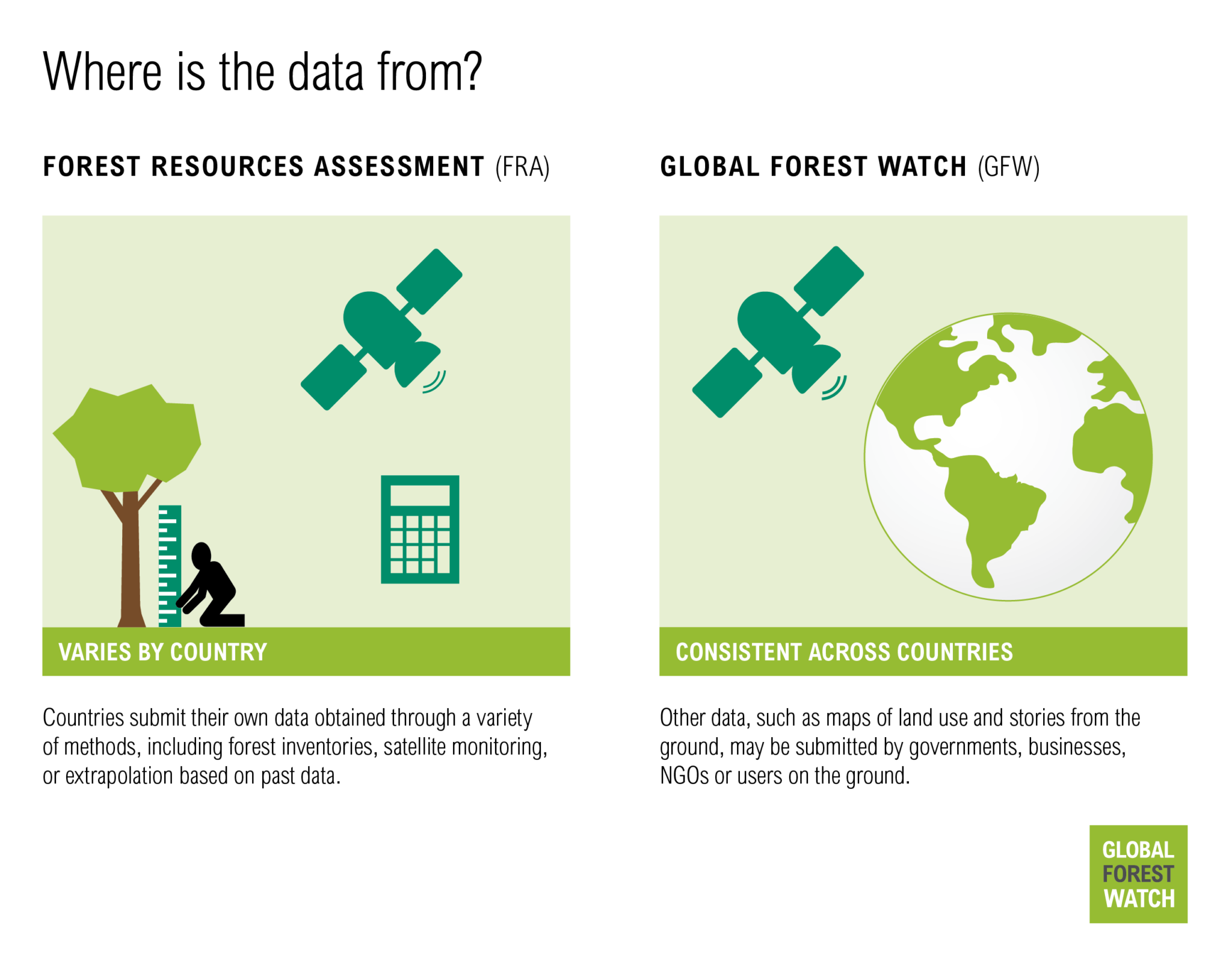

Where is the data from?

FRA compiles official government statistics on forest-related information. This data is self-reported by countries and can come from different sources using a variety of methods, including national forest inventories (NFIs), academic studies, government registries or district forest offices. Remote sensing (RS) is becoming more frequently used as an input into some nationally reported data. Although FAO provides guidelines on what and how to report, in reality, many countries employ their own definitions and methods.

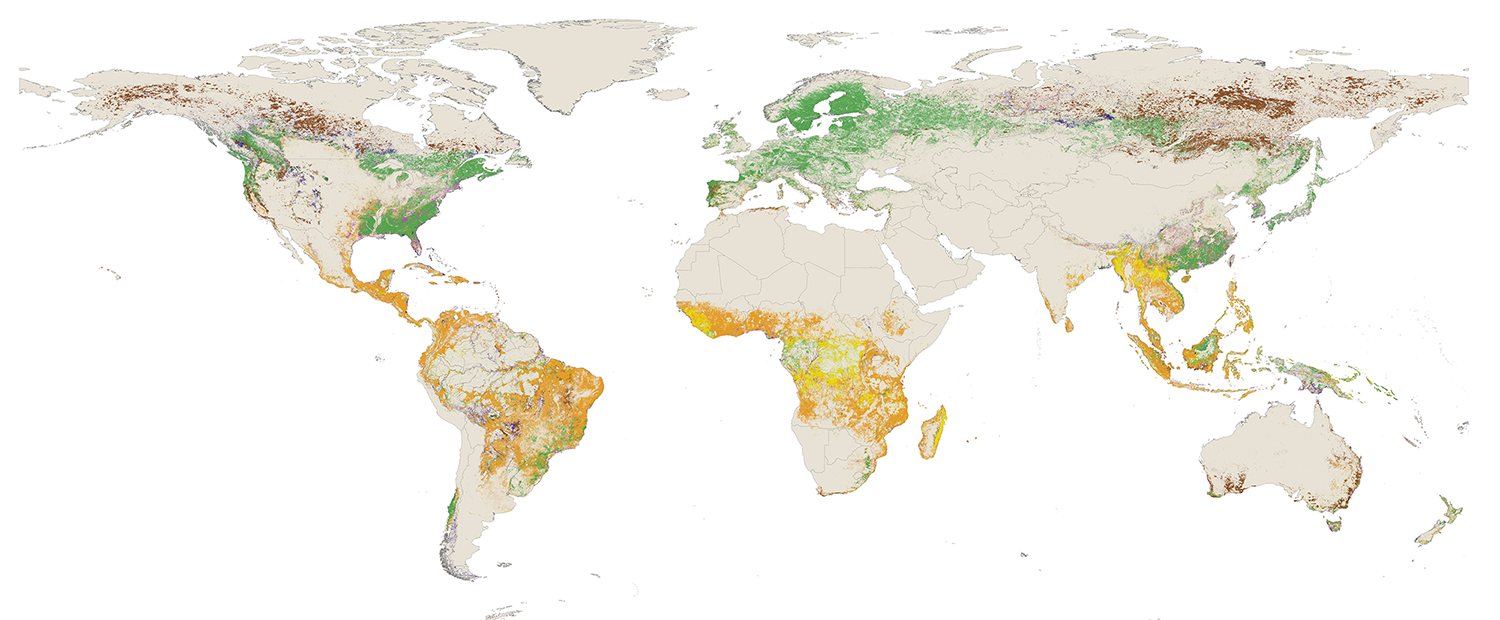

GFW features data that is based on satellite data, providing an independent, transparent and globally consistent record of Earth’s land surface and how it is changing. This record enables consistent comparisons across countries and over time.

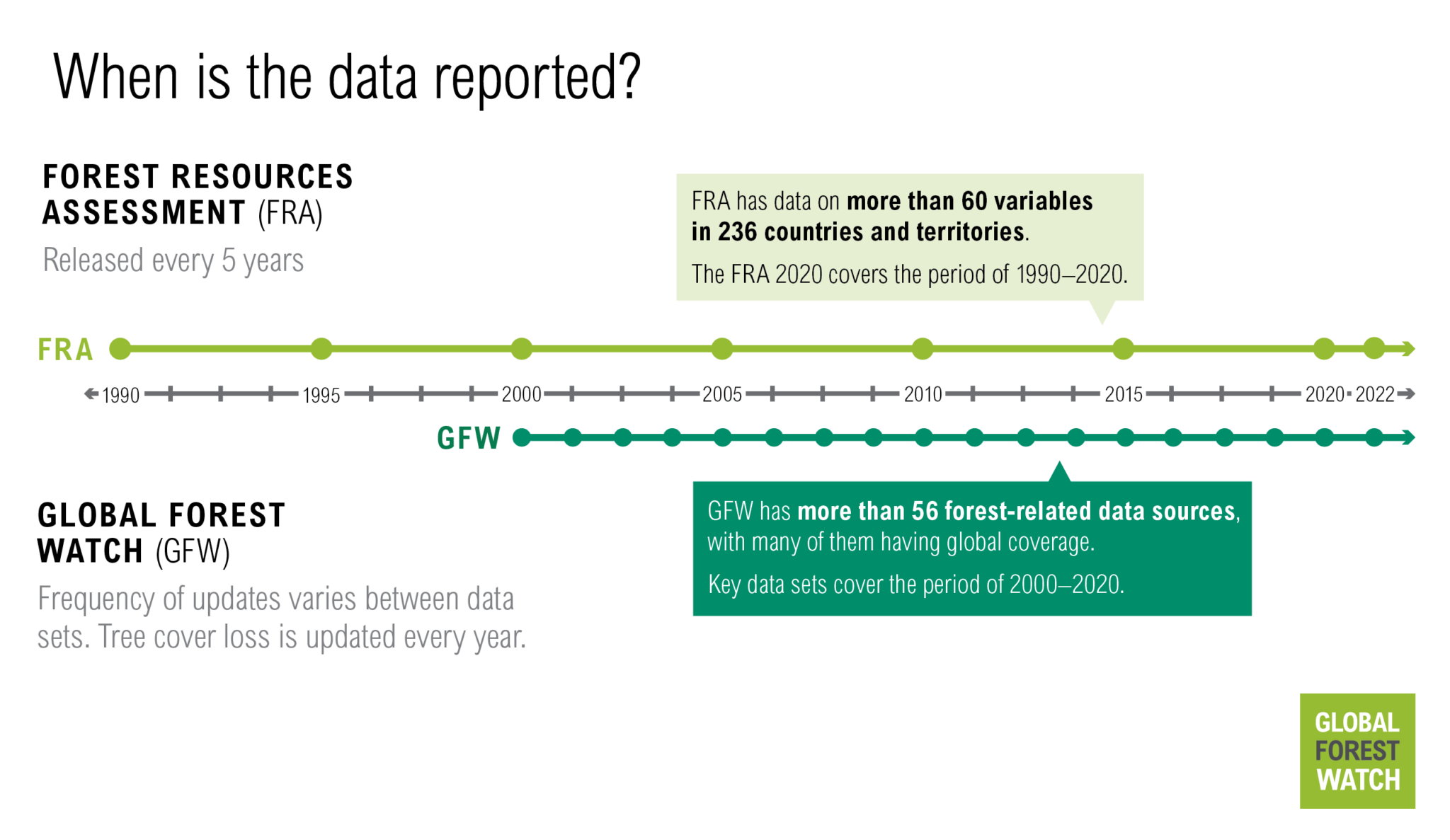

When is the data collected and reported?

FRA reports are released every 5 years based on countries’ reported information. Some countries update their forest information systems frequently, while others update them only every 10-20 years, meaning some FRA reports are based on older data. When country reports are unavailable, the FAO fills in gaps using available literature and expert estimates. A study examining the 2020 FRA data sources showed the most recent years in which RS and NFI data were collected and found that although many countries use data that are only a few years old, there are a number of countries using data over 30 years old.

GFW’s tree cover loss data set is updated each year with the previous year’s data. GFW’s net change and gain data covers the 20-year period from 2000 to 2020, with plans underway for more frequent updates.

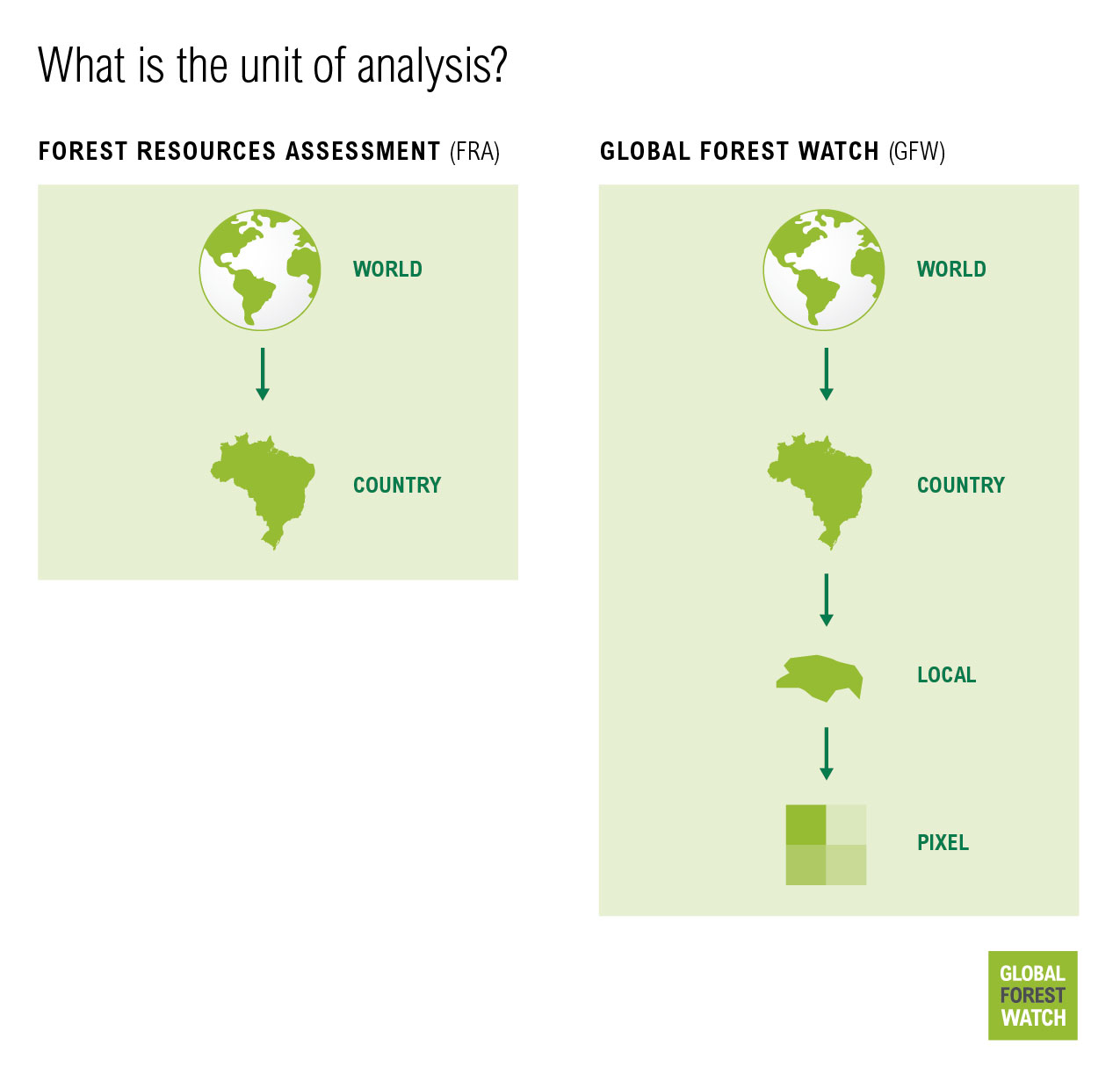

What is the unit of analysis?

FRA collects statistics at the national scale, which are aggregated to provide insights about forest change dynamics regionally and globally.

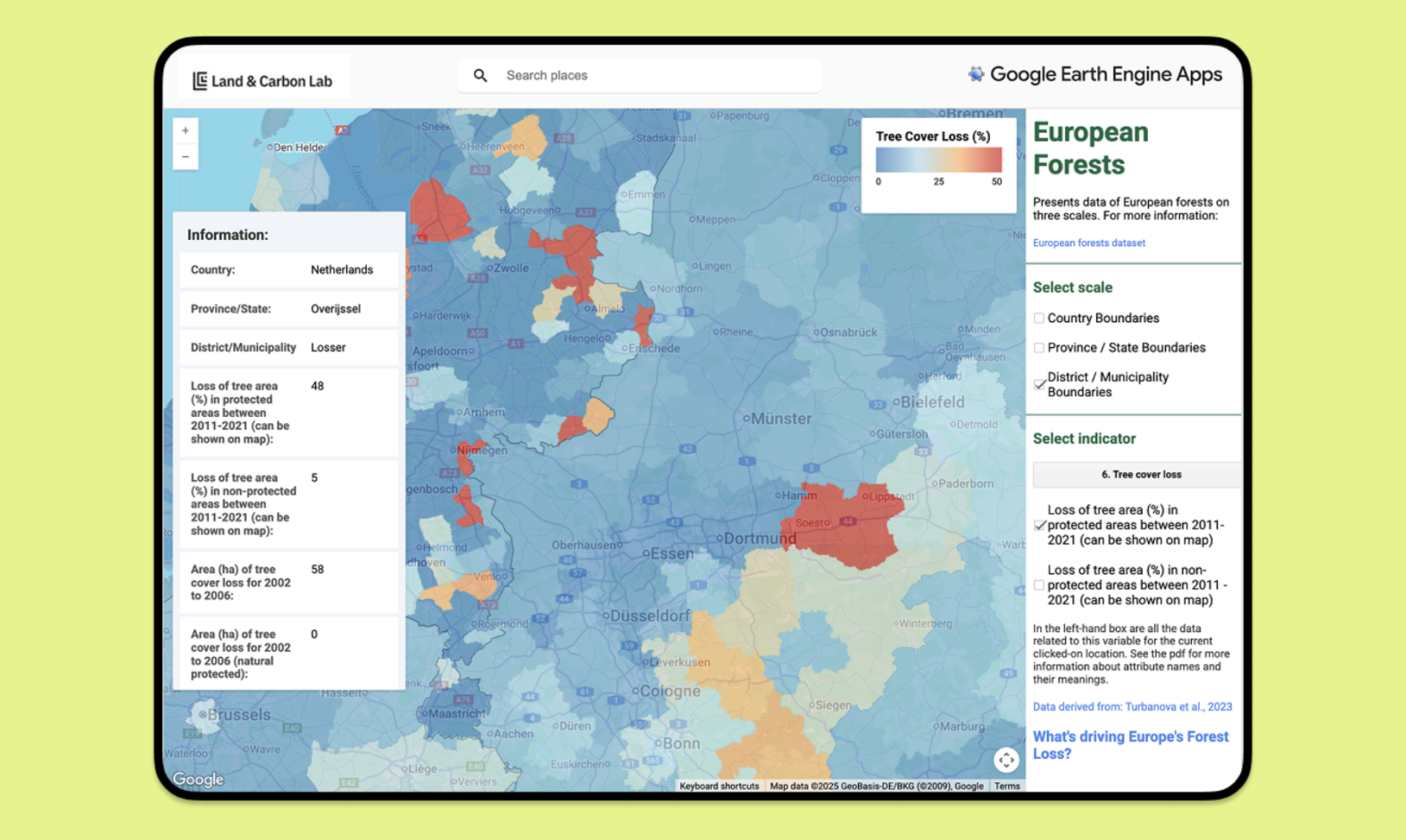

Satellite-based data on GFW records changes in forest area by dividing Earth’s land surface into pixels. These pixels — which for most data on forest area and change are 30 m by 30 m in size — can then be aggregated to show changes over larger areas of interest. This modular format means that in addition to understanding forest dynamics at global, regional and national scales (as with the FRA), users can also monitor changes within custom areas of interest, such as a specific national park in their country, a provincial district, an Indigenous territory or even their own backyards.

What does it all mean?

How one defines forest, deforestation, reforestation and forest expansion is at the heart of the confusion and controversies surrounding these two data sources. Critics of FRA point out that country-reported data may be outdated, inconsistent, incomplete or based on non-transparent methods. In addition, FAO’s net forest change statistic (which is the only forest change variable presented for many countries) provides an overly optimistic view of global forest trends since by their definition, the loss of natural forests — rich in biodiversity and carbon — can be offset by expansion of tree plantation monocultures. The same applies for GFW’s net change information when viewed without the contextual data sets.

Meanwhile, critics of GFW claim that satellite-based monitoring has fundamental limitations on what can be observed from satellites, and that tree cover loss creates an overly pessimistic view since these data lump together permanent and temporary loss of tree cover within natural forests and tree plantations. In the case of FRA, temporary loss is not included in deforestation information.

Ultimately, neither GFW nor FRA is perfect or complete, but they both have important, and complementary, applications.

When might I use GFW or FRA?

Bottom-up approaches like FRA benefit from locally appropriate methodologies, customization of data and use of country definitions — although many countries follow the FAO’s standard definitions. FRA is more comprehensive in scope, ranging from biophysical to socio-economic and legislative variables. FRA’s data will be relevant for those that have a broad interest in the state of forests in a country and how they are being managed.

However, FRA’s data is only reported on a national level and cannot be used for assessing regional differences within countries. GFW’s spatially precise updates on tree cover loss allow users to track where changes in tree cover are happening on a sub-national level. GFW also offers more consistency in methods and definitions across geographies for making comparisons across countries.

GFW currently provides more frequent tree cover loss information (annually) than FRA does on deforestation, while FRA currently provides more frequent updates on forest expansion than GFW does on tree cover gain — though GFW will eventually provide annual tree cover gain data. FRA’s figures also reflect tree planting initiatives that are too recent to be picked up by satellite data, although not all of these projects are successful.

In the end, the differences between GFW and FRA reveal strengths and shortcomings of both sources that make them appropriate for different applications, meaning that both are useful to understand what is happening with the world’s forests.

Rachael Petersen and Octavia Payne contributed to a previous version of this blog.