Oil Exploration and Extraction Threatens South American Mangrove Forests

Sometimes described as coral reefs of the forest for the vast diversity of organisms they support, mangrove forests are one of the Earth’s most varied ecosystems. From above, they might look like any other forest, but beneath their canopy, mangroves’ intricate root systems are home to a wealth of marine life. But as human development and demand for resources have increased, these ecosystems have become increasingly threatened.

Historical data shows that nearly half of the world’s mangrove forests have been lost over the past 50 years. Global Mangrove Watch has been tracking the loss of these forests since 1996. It is estimated that between 1996 and 2016, approximately 973,600 hectares of mangroves were lost. While major drivers of loss include coastal development and conversion to aquaculture — especially for shrimp farming— inland and offshore oil spills represent a lesser known but substantial threat to these critical forests.

The value of mangroves

Restricted to the tropics and the subtropics, mangrove forests serve as habitats for numerous fish, invertebrates and mammals, including tigers and monkeys. Their roots are submerged in tidal waters, acting as nurseries for coral reef fish and seafood staples such as sea trout and sea bass.

Mangrove forests are vital to the livelihoods of coastal communities. Mangrove wood is rot- and insect-resistant, which makes it a valuable building material in the tropics. The complex root systems also provide a natural barrier against erosion, protecting coastlines against flooding during hurricanes and typhoons and increasing coastal resilience. According to an International Climate Initiative report, mangroves reduce flooding for more than 18 million people around the world. Without mangroves, damages from floods would increase by 16 percent, costing coastal communities an additional $82 billion USD annually.

The complex root systems of mangroves provide habitat for a wide array of marine species. Photo by Riccardo Maria Mantero/ Flickr.

The complex root systems of mangroves provide habitat for a wide array of marine species. Photo by Riccardo Maria Mantero/ Flickr. Mangrove forests are also valuable for their carbon storage capacity. Researchers estimated in 2019 that mangroves stored approximately 5 billion metric tons of carbon (including both above and below ground biomass and soil) in 2000— the equivalent electricity usage of 3.2 billion US homes for an entire year. Destruction of mangrove forests means this stored carbon re-enters the atmosphere, contributing a disproportionate amount to global greenhouse gas emissions for an ecosystem that makes up just 0.03 percent of the earth’s surface. According to the Conservation International CEO M. Sanjayan, “about 6 percent of global emissions comes from the destruction of this tiny sliver of habitat,” equaling the carbon dioxide emissions of both France and Germany combined.

The impacts of oil

Oil and natural gas extraction pose a significant threat to mangrove ecosystems. Oil spills from offshore rigs can occur due to human error, equipment failures or natural disasters like hurricanes. Oil released during a spill coats the trees’ root systems, preventing uptake of water and leading to death by dehydration. Heavy metals and other toxins present in crude oil are also absorbed through the roots, weakening and poisoning the trees. Once a spill has occurred in a mangrove forest, there are very few avenues for remediation, as many common cleaning agents are toxic to vascular plants. The effects of oil damage can last more than 25 years after the initial spill.

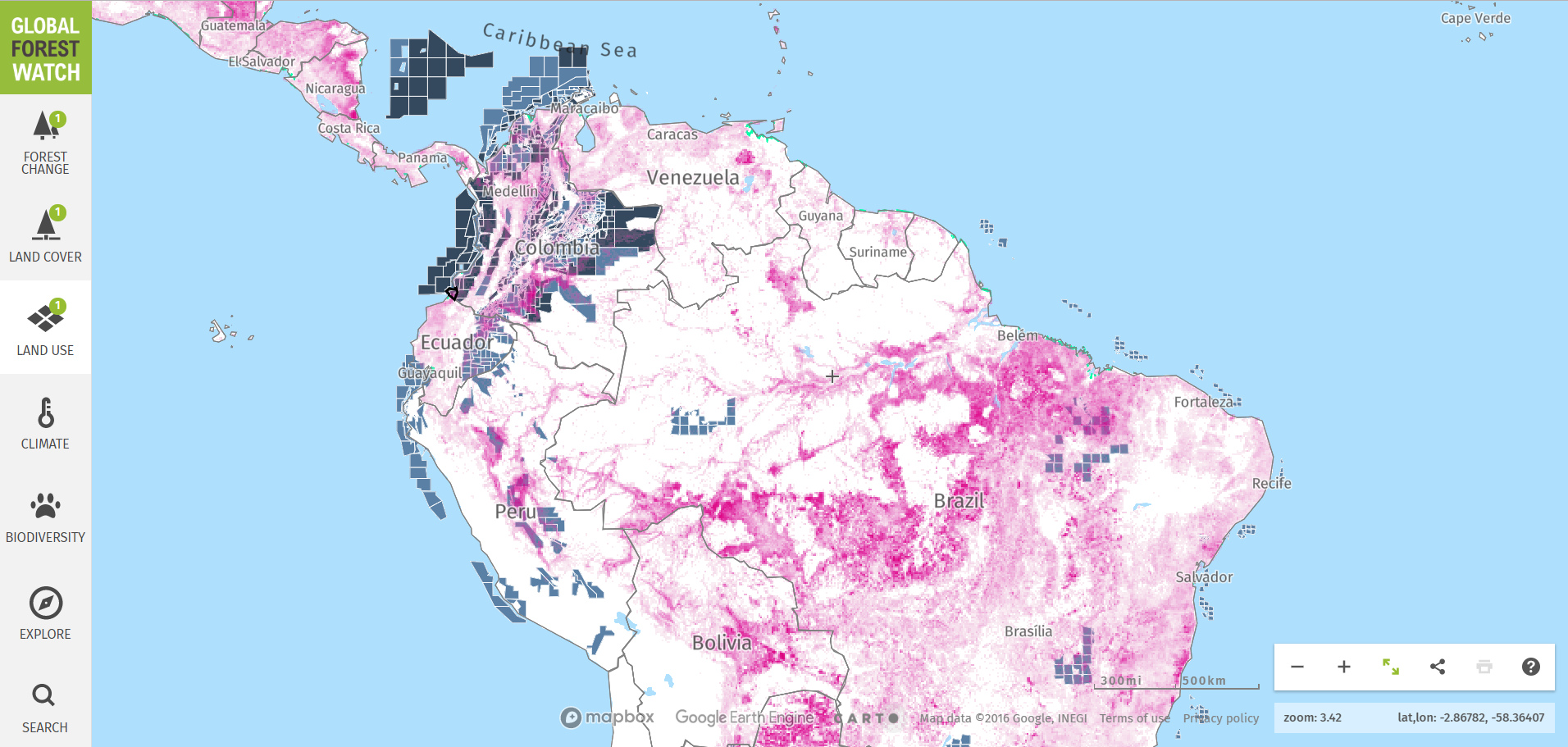

Global Forest Watch (GFW)’s new oil and gas concessions dataset shows the location of over 1,000 concessions across Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru are set aside by the government for exploration and extraction. The data was collected from the national government sources in each country. GFW’s dataset combines the international data together to provide a clearer picture of the distribution of fossil fuel activity across South America.

Concession data is available for five oil producing countries in South America.

Concession data is available for five oil producing countries in South America.Concessions include both areas of offshore and inland drilling. While the dispersion of oil after a spill depends on ocean or river currents, proximity to these oil concessions indicates risk to mangroves.

In Colombia, mangroves grow adjacent to oil concessions along the coast. Much of the country’s southwestern shore is both lined by mangroves and earmarked for oil and natural gas extraction. In June 2015, the Revolutionary Armed Forces attacked a pipeline in the Nariño province, causing more than 10,000 barrels to spill into surrounding rivers and streams that drained into Tumaco Bay. The oil passed through various spill control points and reached the mangrove swamps on the coast. According to the Environmental Minister, ecosystem recovery could take up to 20 years.

Oil spills in these countries happen with concerning regularity. In Peru alone, the government owned petroleum company Petroperú reported that between 2016 and 2018 the company was responsible for 23 oil spills, threatening a variety of ecosystems both on land and offshore. Across the world, other mangrove forests have also felt the effects of spills. In 2014, tens of thousands of tons of oil spilled into the Sundarbans in Bangladesh, a mangrove forest famed for its critical tiger habitat.

Mitigating mangrove loss

Legal action was taken against Petroperú for pumping with a faulty pipeline, but the damages from spills still linger, impacting local and indigenous communities. In Bangladesh concerns for an already threatened tiger population were heightened by the spill. One year following the accident, a census of the Sundarbans’ tiger population showed the population had dropped to just 200 from 440 in 2004.

Wild Bengal Tigers. Photo by Bernie Catteral/Flickr

Wild Bengal Tigers. Photo by Bernie Catteral/Flickr Although spills happen with alarming frequency in regions with significant biodiversity, attempts have been made to minimize the impact of resource extraction on the environment. In 2015, the Colombian government declared six new national parks to prevent mining, drilling and other commercial activities. The Tumaco Bay mangrove forests are under consideration as an additional park, but have not yet been officially designated.

While oil and gas concessions are currently only available on GFW for five countries in South America, GFW hopes to expand this data across the tropical region. As exploration and extraction continues, it is important to keep a close eye on where these activities overlap with mangroves and other forests, with the hope that further impacts can be minimized.