How Rainforests are Formed, and How They are Being Destroyed

Faizal Abdul Aziz/CIFOR

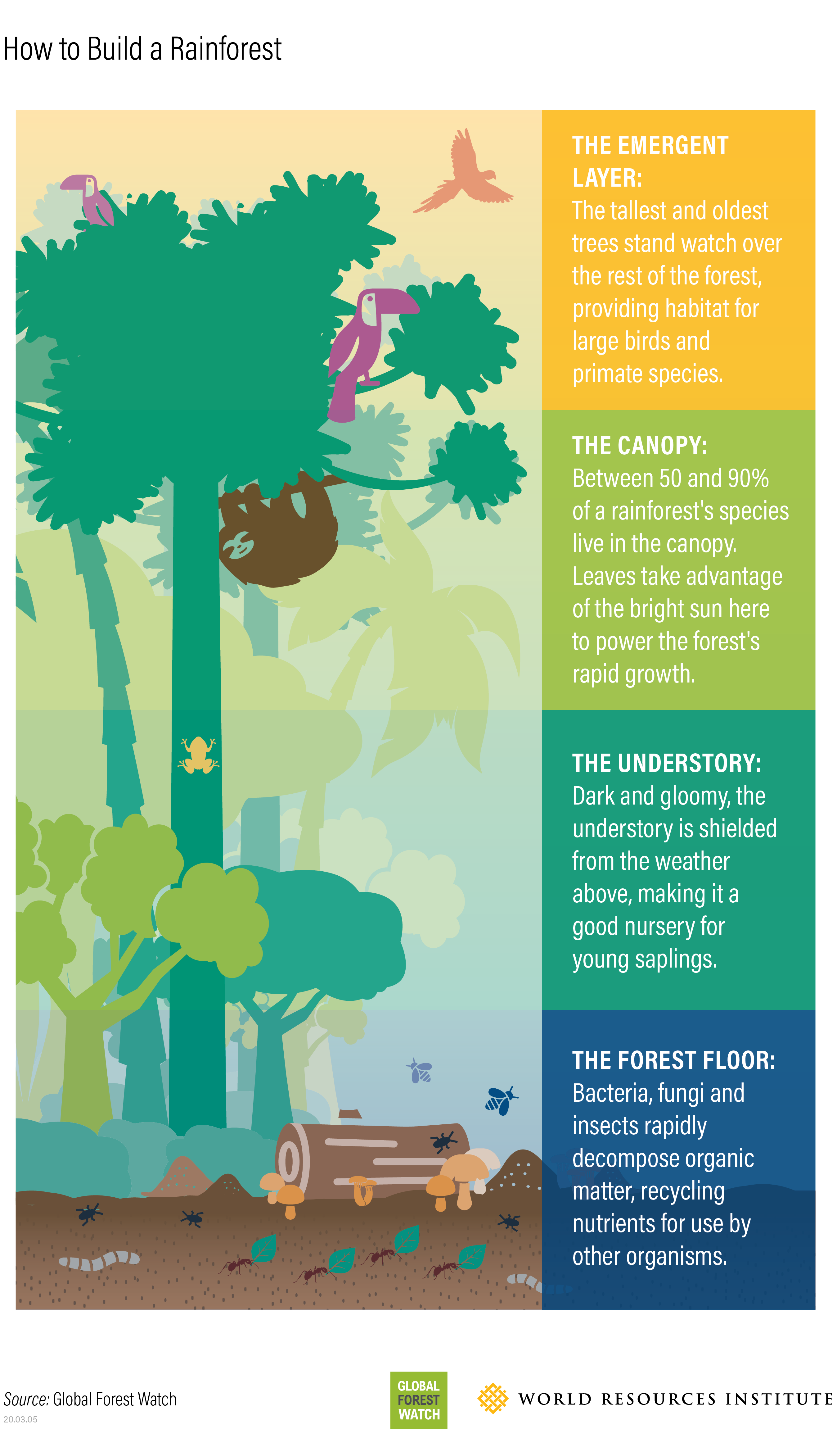

Tropical rainforests are one of the world’s most complex ecosystems. These hot and humid forests harbor millions of species—10 percent of the world’s known species can be found in the Amazon alone—which together form a unique structure that rises in stories from the forest floor to the tops of the tallest trees. Each of these layers holds its own unique community of plants, animals and other creatures that interact to create a rainforest. This complex ecosystem is a sum that is truly more than its parts, but its complexity means that disturbances to individual layers are in fact threats to the entire forest’s natural order.

The rainforest floor: Where dead things go to… well, die

Rainforests, like all forests, begin with the soil. Despite the vast amount of life it supports, rainforest soils are actually very nutrient poor, lacking minerals like phosphorus, calcium and magnesium which typically come from weathered rocks and earning them the moniker “wet deserts”.

What the forest floor is rich in however, is fungi, bacteria and insects that drive the process of decomposition. Because of the hot and humid environment, the nutrients present in organic matter are cycled out of the soil and into growing vegetation extremely rapidly. Animals or bits of foliage that die and fall to the forest floor are quickly scavenged by other organisms to support the forest’s rapid growth.

This hungry system is therefore strongly impacted by anything that interferes with the flow of nutrients. Hydroelectric dams, for example, can halt the flow of sediments downriver. There are currently 140 dams either built or under construction in the Amazon basin that are trapping nutrients behind their concrete walls.

What the rainforest floor lacks in nutrients it makes up for in carbon storage. Carbon from organic matter is stashed away in the soil over centuries of forest growth, yet it can be released in a matter of years. Clear cutting forests unlocks the carbon stored in forest soils, making it more likely to be released into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.

The understory: The rainforest’s dark basement shelter

One layer up from the forest floor is the understory. Here light is at a premium. The thick vegetation above means that at most, only about 5% of the bright tropical sunshine will reach the residents of the understory. The plants that grow here have adapted to the shady conditions with wide leaves to trap every fleck of sunlight. Thick canopy vegetation also shields the understory from harsh winds and rain, sheltering growing seedlings.

In a healthy, mature rainforest, the understory will be relatively empty. Thick, scrubby vegetation is indicative of some disturbance that has opened a light gap. Any form of clearing opens up the roof of the forest and the downpour of sunlight favors fast growing shrubs and vines over the slower-growing saplings of keystone tree species. Harsh sun and wind also dries out clearings and the edges of the forest, making them susceptible to burning. When farmers clear rainforest for crops or livestock using fire, the flames can easily escape into the understory of the surrounding forest. These understory fires are often not big enough to destroy large trees, but they do kill small thin-barked trees and young saplings, creating even more dry, dead wood that increases the risk of further fires.

The canopy: A tree top power station

Above the understory and knit together by the thick crowns of the trees is the canopy. Up here it is warm, sunny and crowded, like a popular beach vacation spot. An estimated 50-90% of life in the rainforest lives up in the trees—swinging, squawking and slithering through the branches.

The canopy is the main site of interchange for energy, water vapor and atmospheric gasses like oxygen and carbon dioxide. Canopy leaves act as trillions of tiny solar panels converting the strong sunlight to energy, and water evaporating from the trees contributes to the humid climate around tropical rainforests.

The canopy is also populated by a class of plants called epiphytes, which grow in the “canopy soils” (decaying leaves and organic matter caught in the crooks of tree branches) and pull most of their nutrients from the air. This makes them particularly vulnerable to air pollution. A recent study found that increased levels of nitrogen and phosphorous in the atmosphere from human activity can lead to alterations in the chemical make-up of the canopy soils which could have big impacts on the diversity of canopy life— the same way polluted runoff can cause algal blooms in water.

The emergent layer: Ancient pillars of the forest

The emergent layer is comprised of the oldest and tallest trees. Breaking through the canopy and sometimes reaching over 200 meters above the ground, emergent trees are the “kings” of the rainforest. These keystone hardwood species like Brazil Nut, Mahogany and Kapok provide critical habitat for large birds and primates. This layer is threatened particularly by selective logging practices. Large emergent trees are targeted for their value as timber. Some species of birds like Macaws nest in large cavities found exclusively in these old growth trees and therefore suffer these losses hardest. Additionally, although only one tree is cut, woody vines called lianas that are strung between trees often pull down others as the cut tree falls, and the infrastructure required to move logging equipment into the thick forest tears down trees along the way.

Logging roads expanding into the Peruvian Amazon. Roads like these typically precede further loss in the surrounding forest.

Logging roads expanding into the Peruvian Amazon. Roads like these typically precede further loss in the surrounding forest. One rainforest

Although each layer of the rainforest is distinct, they are inextricably connected—by animals dispersing seeds and plants cycling nutrients up to the canopy and back down again. Research has even shown that trees communicate with each other via mutualistic relationships with fungi. Damage done to one segment of the forest ripples down and outward, often having broader impacts than are immediately visible.

Understanding these connections, both within the forest and to the wider global climate, highlights the need to tread carefully when it comes to rainforests. Their complexity and interconnected structure mean seemingly small actions can cause unexpected damage.