Fighting an Upstream Battle to Protect One of the World’s Tallest Waterfalls

Christel Scheske is a 2018 GFW Tech Fellow. The GFW Tech Fellowship is designed to equip dedicated forest protection advocates from around the world with the skills and technologies to help halt deforestation. Christel lives and works in Peru as a project coordinator for the Conservamos por Naturaleza initiative of Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental

In 2005, German explorer Stefan Ziemendorff stood at the base of what he thought was one of the world’s tallest waterfalls — a waterfall that was, until that moment, unknown to scientists.

Plunging 771 meters (2,529 feet) in two near vertical drops, the Gocta Falls in Amazonas, Peru had been the backdrop of the local Cocachimba community for years before they were recognized as the world’s 16th tallest waterfall. The falls’ global discovery has transformed it into a lucrative tourist destination, attracting travelers looking for a rainforest adventure with a view. Cocachimba now benefits from the tourism with locally-owned hotels and waterfall tours led by community members generating revenue. This rapidly changing social landscape is what drew GFW Tech Fellow and part-time resident of Cocachimba, Christel Scheske, to focus her mapping project on Gocta Falls.

Protecting the forests to protect the falls

The nascent tourism industry surrounding the falls depends heavily on preserving the highlands above them. The ecosystem upstream is a combination of wetlands and forests that drain directly into the Cocahuayco River.

“A lot of the tourism in Amazonas depends on the waterfall continuing to exist in the way it does, and for that you have to protect the water catchment system,” Scheske said.

The watershed is owned by different communities however, which makes enacting protections for it tricky.

“A lot of [Cocachimba community members] have made a lot of money selling land and doing business, and that hasn’t happened for all the other communities who aren’t directly at the entrance to the waterfall,” Scheske said. “It’s delicate.”

Scheske’s project focuses on a budding payments-for-ecosystem-services scheme that has arisen between Cocachimba and Yuramarca— a village upstream of the falls— with Cocachimba paying Yuramarca to protect part of the watershed. The hope is that these payments will create a clear incentive for the upland village to halt activities that could negatively impact the watershed, thereby preserving the waterfall so both communities can continue to benefit from it.

In a typical scheme like this, both villages would agree on the boundaries of the area in question and what actions should be taken to protect it before any payments are made. What Scheske found however, was that informal payments were already being made and there was no way to monitor compliance from upriver.

Piecing the puzzle together

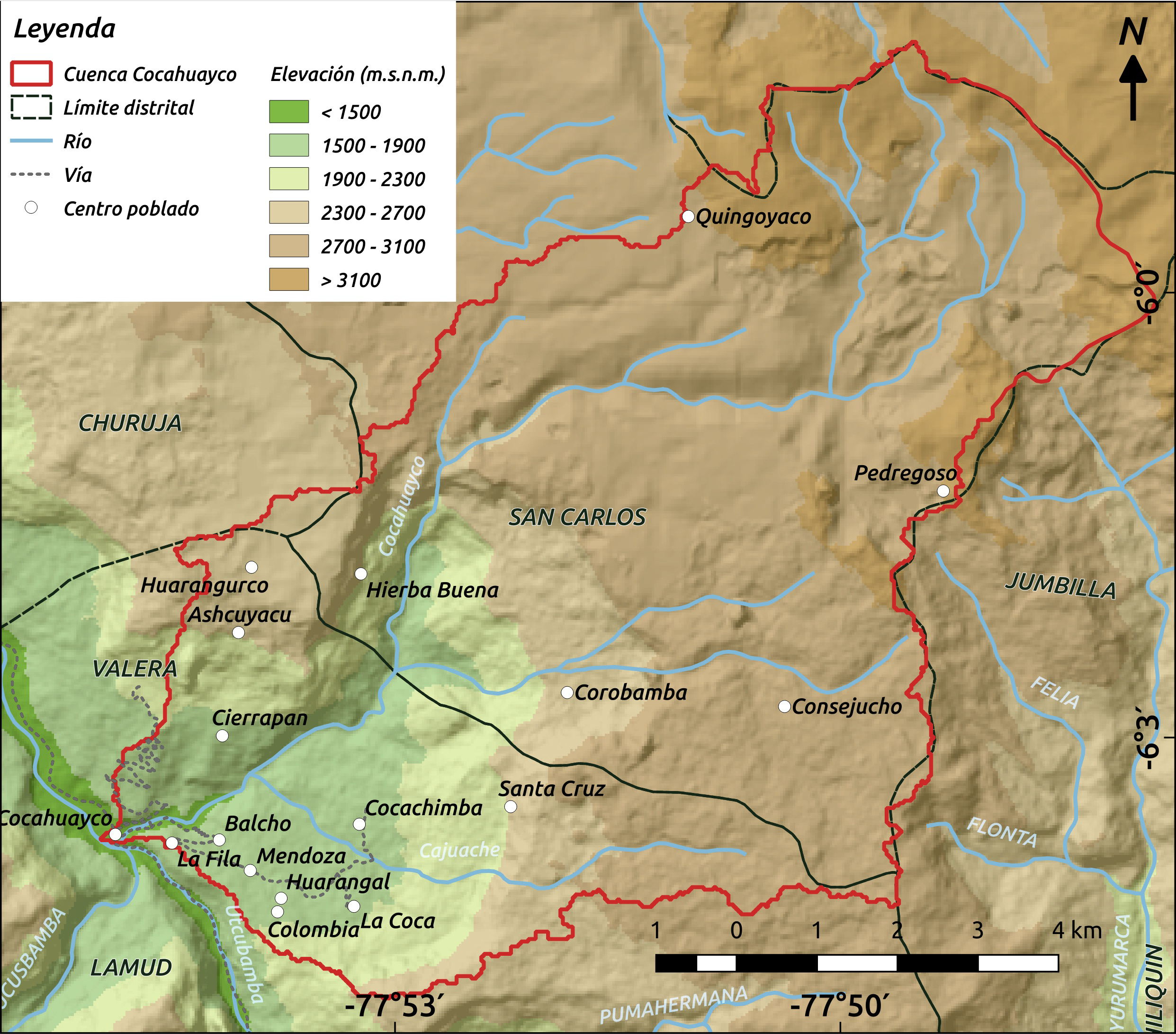

Map of the water catchment area for the Cocahuayco River. By Giulia Curatola and Sandro Makowski.

Map of the water catchment area for the Cocahuayco River. By Giulia Curatola and Sandro Makowski.Scheske’s first goal was to map the surrounding watershed and determine exactly how much land was necessary to protect. Using her grant, Scheske worked with two GIS specialists to analyze the topography and find out where water was feeding into the falls.

Once they had mapped out the watershed, the next step was figuring out who had claim to the land and should therefore be involved in conservation decisions. The team discovered that Yuramarca has been using an area nearly one-fifth the size of the entire watershed but doesn’t seem to have formal land tenure. Other portions of the watershed are owned by families from Cocachimba and yet another piece is owned by the neighboring community of San Pablo which has already declared a section of their land as a private conservation area.

“It’s like a big puzzle that we’re trying to put together,” Scheske said.

The path ahead

Lack of information has proven a challenge for Scheske. Much is still unknown about the falls and the ecosystem surrounding them. Even simple access to accurate maps has been hard to find.

“I’ve run into the problem where somebody has told me that there is a proposal for a regionally protected area… which would probably have a lot of the baseline information that I’m looking for, and all of that information is contained on a CD in that regional government’s office, and it’s too scratched for any computer to read,” Scheske said.

Despite setbacks, Scheske’s team was able to accomplish much of the preliminary mapping and donated two GPS units to Cocachimba to help in future monitoring and mapping of private land plots. Once the community has a full picture of the landscape, they will be better able to formalize their conservation efforts.

Scheske presenting the GFW platform to the Latin American Congress on Private Conservation. Christel Scheske/WRI.

Scheske presenting the GFW platform to the Latin American Congress on Private Conservation. Christel Scheske/WRI.The Conservamos por Naturaleza initiative has received matched funding from the US Fish and Wildlife Service for the coming year, which will allow Scheske to continue her project. She hopes to gather more information about how the land above the falls is currently used, which will help determine what protections need to be put into place.

“Based on our conversations with the community, most of what’s happening is that people are sending up their cows [to graze],” Scheske said “So that impacts the ecosystem but I’m not sure how and to what extent.”

Scheske is excited about the progress they have made towards protecting the Gocta’s watershed but emphasizes that for any conservation project to be successful, the next step after collecting information should be putting it to good use.

“We’re just at this amazing point where there’s so much more information accessible… but at the same time we’re not advancing at the same rate in understanding how to actually use that information to deal with threats that are now so super obvious,” Scheske said. “I think the big challenge is coming up with solutions for dealing with the threats that are as innovative as the information that is being put out there.”

BANNER PHOTO: Gocta Falls as viewed from the valley. Photo by Christel Scheske/WRI.