Zooming In: GFW Small Grant Fund Recipients Discover Endangered Wildlife Threatened by Nicaragua Canal

By Sarah Mann, Wes Sechrest and Christopher Jordan In southeast Nicaragua along the Caribbean Sea lies one of the last pristine forests in Central America and one of two remaining core areas of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor in the country. Iconic species such as jaguars and tapirs roam the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve, with indigenous Rama and afro-descendant Kriol communities settled throughout the intact landscape. However, the Nicaraguan Interoceanic Canal is scheduled to be built right along the northern border of this valuable reserve, putting an already complicated situation in further peril. A new report released by Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), a GFW Small Grant Fund Recipient, and Panthera have identified endangered species corridors that may be bisected by the Nicaraguan Interoceanic Canal. These data have renewed concerns about the future of the jaguar and other species if proper mitigation actions are not taken. Without these genetic pathways, three of Nicaragua’s rarest large mammal species – jaguars, white-lipped peccaries, and Baird’s tapirs – will struggle to find neighboring populations for breeding, which is key to conserving genetic diversity and healthy populations.

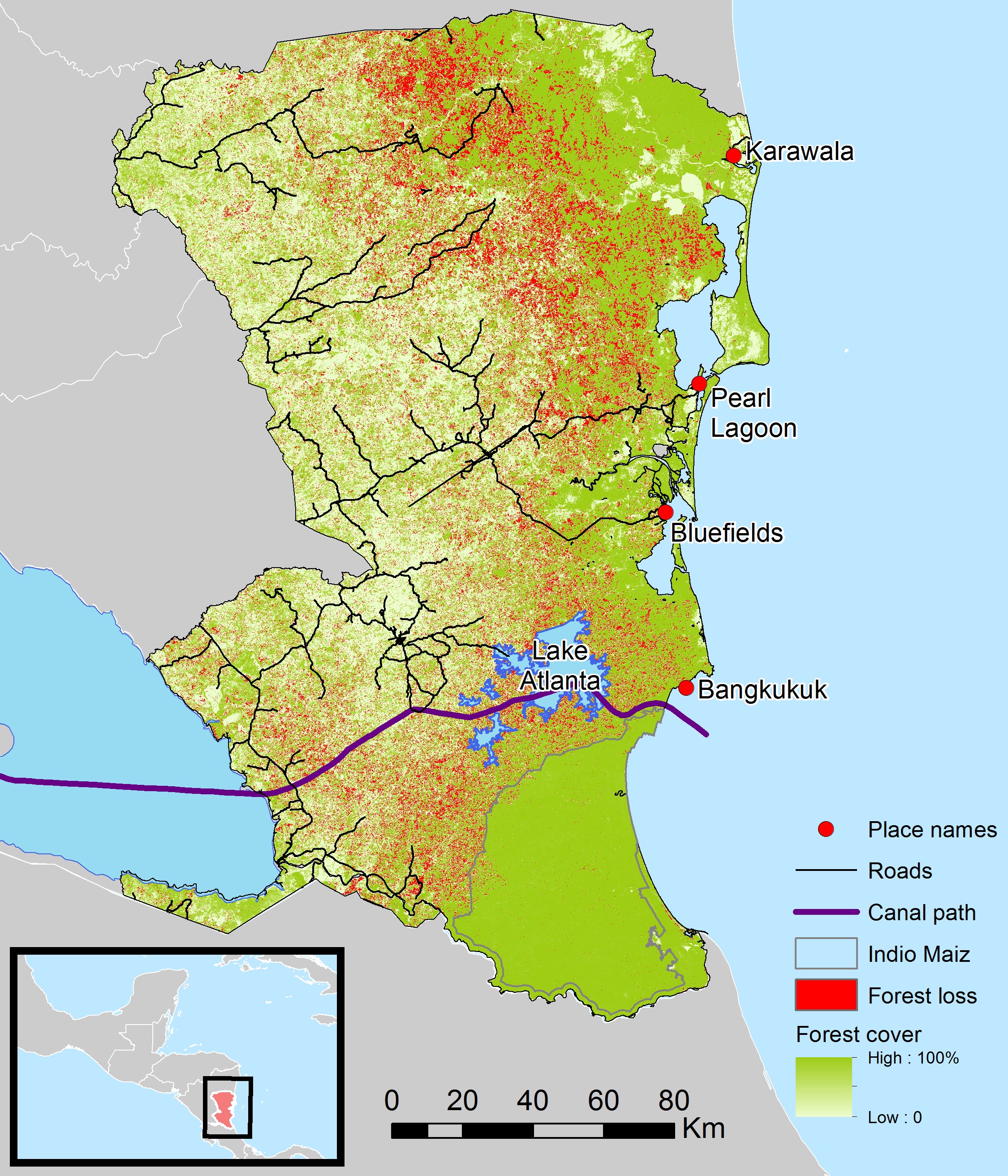

The canal path (purple) borders the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve (solid green) Photo from Global Wildlife Conservation

The canal path (purple) borders the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve (solid green) Photo from Global Wildlife Conservation New threat to an already dire situation

There’s a chance little pristine forest will be left to affect by the time the canal construction reaches the ocean. 15 years ago the indigenous territories of Caribbean Nicaragua boasted some of the largest forests in Central America, but illegal cattle ranching has devastated huge expanses, creeping in from the west and occupying what looks to them like unoccupied forest land. This has significantly diminished habitat for wildlife and threatens the food security and cultural survival of the indigenous peoples who hold legal, communal tenure to the land. “Even in the absence of canal construction, without increased efforts to address the expanding cattle ranching frontier, the country’s remaining Caribbean reserves will effectively disappear within the next 10-15 years,” said Sandra Potosme, Panthera’s Nicaragua Coordinator.

Tree Cover Loss occuring from 2001-2014 slowly encroaches on the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve, an Intact Forest Landscape

Tree Cover Loss occuring from 2001-2014 slowly encroaches on the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve, an Intact Forest Landscape A Community Responds with Forest Monitoring

In response to this pressing concern, GWC has been working with support from the GFW Small Grants Fund to preserve what is left of the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve. GWC is working closely with the local Rama and Kriol community to establish a new group of forest rangers, using a combination of best practice models from other GWC ranger patrols. Global Forest Watch forest cover loss and fires data helps them to identify areas under the greatest immediate threat and to define the rangers’ patrol routes. This is the first time remotely sensed data has been used in this region for this purpose, and offers rangers a link to near real-time technology that could enhance their ability to protect their land. Setting up a patrol in such a vast, remote area with no previous on-the-ground monitoring system is no small task. GWC is starting from scratch, but thinking about long-term protection of the land, and the local indigenous communities and their local and territorial leaders have been extremely supportive of the program. With no forest rangers to monitor the land, cattle ranchers have been steadily eating away at the edge of the forest. Regular patrols should help the cattle ranchers understand the forest is actually a biological reserve that is technically occupied.

Armando John and Pablo Solano from the Rama community work through an exercise in GPS during a training workshop in Indian River.

Armando John and Pablo Solano from the Rama community work through an exercise in GPS during a training workshop in Indian River. With help from GWC, these new forest rangers are being trained to use GPS, ground-truth data, and expose what is happening on their land. “The Rama and Kriol people have conserved the Indio Maíz Reserve for centuries, but until recent years have never faced a threat like the advancing cattle ranching frontier,” says Wes Sechrest, chief scientist and CEO of Global Wildlife Conservation, “The forests and wildlife are an important part of their cultural identity and survival. We are working with the forest rangers and territorial leaders to develop and implement long-term strategies that will help protect the most biologically and culturally important areas of their territory.”